Story Goal Explained

A story's Goal is most often found in the Overall Story Throughline for stories written in our culture. Apart from that bias, the story Goal might just as properly be in any of the four Throughlines. As we now consider how to select the Goal for our story, we need to know a little bit more about what a Goal does for an audience. What kinds of control over our audience we can exercise simply by choosing where we place the Goal?

An audience sees a story's Goal as being the central objective of the story. The goal will be of the same nature as the Concern of one of the four Throughlines. Which one depends on which throughline an author wants to highlight in his storytelling. For example, suppose your Main Character and his experiences are the most important thing to you, the author. Then you will most likely want to make the Main Character's Concern your story Goal as well. On the other hand, if your story is about a problem that is affecting everyone, you will probably want to make the Overall Story Throughline Concern your story Goal.

Each throughline will have its own Concern. When the audience considers each throughline separately, it will focus on that Concern as being the principal objective from that point of view. When the audience considers the story as a whole, however, it will get a feel for which throughline is most highlighted by the author's storytelling, and will see that throughline's Concern as the overall story Goal.

Since emphasis is a gray-scale process, the story Goal may be a highly focused issue in some stories and of lesser concern in others. In fact, you may stress all four throughlines equally which results in an audience being unable to answer the question, what was this story about? Just because no overall Goal is identifiable does not mean the plot necessarily has a hole. It might mean the issues explored in the story are more evenly considered in a holistic sense, and the story is simply not as Goal-oriented. In contrast, the Concern of each Throughline must appear clearly in a complete story. Concerns are purely structural story points developed through storytelling, but not dependent on it.

When selecting a Goal, some authors prefer to first select the Concerns for each Throughline. In this way, all the potential objectives of the story are predetermined and the author then simply needs to choose which one to emphasize. Other authors prefer not to choose the Goal at all, since it is not an essential part of a story's structure. Instead, they select their Concerns and then let the muse guide them in how much they stress one throughline over another. In this way, the Goal will emerge all by itself in a much more organic way. Still, other authors like to select the Goal before any of the Concerns. In this case, they may not even know which Throughline the Goal is part of. For these kinds of author, the principal question they wish to answer is, what is my story about? By approaching your story Goal from one of these three directions, you can begin to create a storyform that reflects your personal interests in telling this particular story.

There are four different Classes from which to choose our Goal. Each Class has four unique Types. In a practical sense, the first question we might ask ourselves is whether we want the Goal of our story to be something physical or something mental. By deciding this we are able to limit our available choices to Situation or Activity (physical goals), or Fixed Attitude or Manipulation (mental goals). Instantly we have cut the sixteen possible Goals down to only eight.

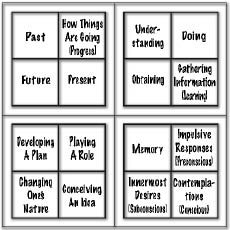

Next we can look at the names of the Types themselves. In Situation: Past, Progress, Present, and Future. In Activity: Understanding, Doing, Learning, and Obtaining. In Fixed Attitude: Memory, Impulsive Responses, Contemplation, and Innermost Desires. In Manipulation: Developing A Plan, Playing A Role, Conceiving An Idea, and Changing One's Nature. Some are easy to get a grip on; others seem more obscure. This is because our culture favors certain Types of issues and doesn't pay as much attention to others. Our language reflects this as well so even though the words used to describe the Types are accurate, many of them need a bit more thought and even a definition before they become clear. (Please refer to the appendices of this book for definitions of each.)

Whether you have narrowed your potential selections to eight or just jump right in with the whole sixteen, choose the Type that best represents the kind of Goal you wish to focus on in your story.