Variations

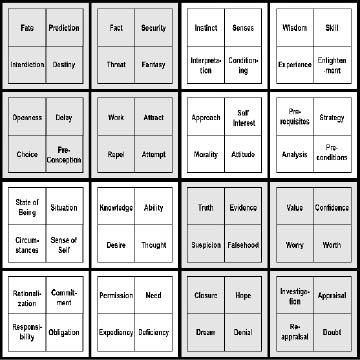

When we subdivide the Types, we can set up four different VARIATIONS of each. This creates the extended chart below:

Situation Variations Activity Variations

Manipulation Variations Fixed Attitude Variations

Now we can finally begin to see some familiar thematic topics: Morality, fate, commitment, and hope, for example. We can also see some unfamiliar terms about theme that we may not have considered before. As before, Western culture (as do all cultures) favors certain areas of exploration and almost ignores others. For an author who wishes to explore new ground, these unfamiliar terms provide a wealth of choices. For the author who writes for the mainstream, all the old standbys are there, but with much more detail than before.

You will not find terms on this chart like "love" or "greed." Although these concepts figure prominently in many discussions of theme, they are more descriptive of subject matter, rather than the perspectives one might take about that subject matter. For example, suppose we decide to write a story about love. All right, what kind of love? Brotherly love? Romantic love? Paternal, lustful, spiritual, or unrequited love? Clearly, love is in the eye of the beholder. In other words, love is shaded by the nature of the object that is loved.

In our chart of Variations, we find terms such as "Attraction", "Obligation", "Desire", or "Instinct", each of which can be used to describe a different kind of love. For example, love in the context of Attraction could be physical love or puppy love. Love in the context of Obligation could be parental love or familial love. Love in the context of Desire could be passionate love or obsessive love. Love in the context of Instinct could be animal love or love at first site, and so on. Use the Variations to say something specific about Love.

Similarly, you won't find "Greed" on this chart, but you will find "Self-Interest" (near the lower left corner of the Activity Variations). "Self-Interest" is not as emotionally charged as "Greed." It more clearly defines the issues at the center of a rich man's miserliness, a poor man's embezzlement, and a loving parent who must leave her child to die in a fire to save herself. And other Variations such as "Fantasy", "Need", "Rationalization", or "Denial" each reflect a different form of "Greed".

It is not our purpose to force new, sterile and unfamiliar terminology on the writers of the world. It is our purpose to clarify. So, we urge you to pencil in your favorite terms to the chart we have provided. Stick "Love" on "Attraction," place "Greed" on "Self-Interest," if that is how you see them. In this manner, you create a chart that already reflects your personal biases, and most likely incorporates those of your culture as well. The original bias-free chart, however, is always available to serve as a neutral framework for refining your story's problem.

As a means of zeroing in on the Variation that best describes the thematic nature of your story's problem, it helps to look at the Variations as pairs. Just as with characters, the Variations that are most directly opposed in nature occur as diagonals in the chart. A familiar dynamic pair of Variations is Morality and Self-Interest. The potential conflict between the two emerges when we put a "vs." between the two terms: Morality vs. Self-Interest. That makes them feel a lot more like the familiar thematic conflict.

Later we shall return to describe how each dynamic pair in the chart can form the basis for a thematic premise in your story. We will also show how this dynamic conflict does not have to be a good vs. bad situation, but can create a "lesser of two evils" or "better of two goods" situation as well.